I received this message (edited for privacy) in my Facebook inbox the other day from a friend in Toronto.

|

Hey Tanya! You’re a housing person. I’d like your input. I’m on ODSP but my health is improving. I want to move but I’m not sure I will go off ODSP for another year or so. I’m trying to make sense of how to potentially hook up some subsidized housing. I know it won’t likely happen overnight, but I want to do lots of research, and get my name on as many lists as I can. I’m already on a list related to my illness category. Also, it never hurts to be on lists that might come up someday in the future anyway. Today I called “Housing Connections” and they were very discouraging, telling me that there is a 20-year wait list for a 1 bdrm. I also went to the Toronto Housing Coop page, but the ones with open wait lists are areas I don’t want to live in. What I would really like is to get my hands on a list of buildings that have been built in the last 20 years, in good neighbourhoods, that are subsidized. Also, is the 20-year wait time from Housing Connections realistic? Thanks |

Unfortunately, I didn’t have much good news to give my friend. An increasing number of people are precariously housed and low vacancy rates, low minimum wages/social assistance rates and a lack of affordable housing make it hard for people across the country to find rental units.

I did recommend that they look up market and affordable rent units in Toronto Community Housing Corporation’s (TCHC) portfolio. As TCHC and other social housing providers move towards more mixed rental housing projects there are an increased number of market and affordable rent units becoming available. 93% of TCHC tenants are subsidized with rent-geared-to-income (RGI) housing which means tenants don’t pay anymore than 30% of their income on rent. Above this you are considered to be in ‘core housing need’.

The remaining units are priced on the lower end of market rent and therefore are assumedly more affordable. For market rent units the rate is set to match local rental rates and there is no income cap. For affordable units the guidelines state that the rent is set “at or below average market rent”. These affordable units have an income cap based on cost/size of unit under which the household’s gross income cannot exceed 4 times the amount of rent.

While this is great in theory and assures that people who have the resources to pay market aren’t living in units aimed at people with lower incomes the rents are still not affordable to someone on social assistance or working a minimum wage job.

For example, someone working full-time in Ontario makes $22,862.40 gross annually or $1905.20/month.[1] With a rent of even $822 this is 43% of their gross income. With the higher rents of $979 and $1161 this equates to 51.4% and 61% (respectively) of their income. While a single person would likely be able to handle the 43% and live in a bachelor unit, a family would need a larger unit. If that is the only income than they would automatically be in ‘severe housing need’ and yet, they may spend years on the waiting list for RGI housing.

Calculation guide for an affordable rental unit

|

Type of unit |

Sample monthly rental rates |

x 12 months x 4 = |

Maximum household annual gross income |

|

Bachelor |

$822 |

x 12 months x 4 = |

$39,456 |

|

1-bedroom |

$979 |

x 12 months x 4 = |

$46,992 |

|

2-bedroom |

$1,161 |

x 12 months x 4 = |

$55,728 |

This fall, the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness will be releasing some up-to-date information on vacancy rates and housing affordability across the country. In the meantime, what we do know is that it is extremely challenging for people without a lot of income – especially those on social assistance, receiving pensions or making minimum wage – to be able to afford to pay for the housing that they need.

The problem exists across the country, in large urban areas and small rural communities. In this week’s blog about the release of Housing First in Rural Canada: Rural Homelessness & Housing First Feasibility Across 22 Canadian Communities, Dr. Alina Turner explained that rural communities have a strained housing and service infrastructure. She says, “Bigger communities often note the lack of affordable housing and essential supports (mental health, addictions, domestic violence services, etc.) to be a major challenge in addressing homelessness. In rural centres, this issue is even more acute. There simply isn't enough funding and service capacity to offer the diverse supports needed. When it comes to assisting homeless persons with complex addictions and mental health issues, these communities have to point people to move to larger centres. Many rural communities don't have formal rental sectors, never mind affordable housing stock.”

The problem exists primarily because there are not a lot of new housing projects that have been built around the country, especially compared to the ‘golden years’ of the 1970s and 1980s when the federal government was solidly in the rental housing market and made a strong investment in co-ops and social housing. The downloading of housing to the provinces/territories in 1993 (and subsequent downloading to the municipalities in many areas) marked the end of Canada’s major housing investment. Canada, as we have said here before, remains the only country in the industrialized world without a national housing strategy.

The Ontario data shows that in 2012 there were 158,445 households waiting for RGI housing as of December 31, 2012. That’s 3.05% of households in Ontario. The report explains that 18,378 households or about 11% of households on the waiting lists were housed. They had experienced an average wait time of 3.2 years. But for every household housed there were three new applications added to the wait list.

The numbers in Ontario ranged depending upon size of the community and housing market. In Toronto the number of households (not people…households) waiting for subsidy is 72,696, in Niagara 5,831, in Ottawa 9,717 and in Cochrane 1,458.

This situation is echoed across the country. According a Huffington Post article the Big City Mayors Caucus of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) says:

- “Calgary and Waterloo have more than 3,000 families on wait-lists for affordable housing, and Metro Vancouver has 4,100.”

- “The average price of a new home more than doubled from 2001 to 2010.”

- “Saskatchewan needs 6,500 to 7,000 new housing starts a year to meet demand and attract workers and Metro Vancouver needs an estimated 6,000.”

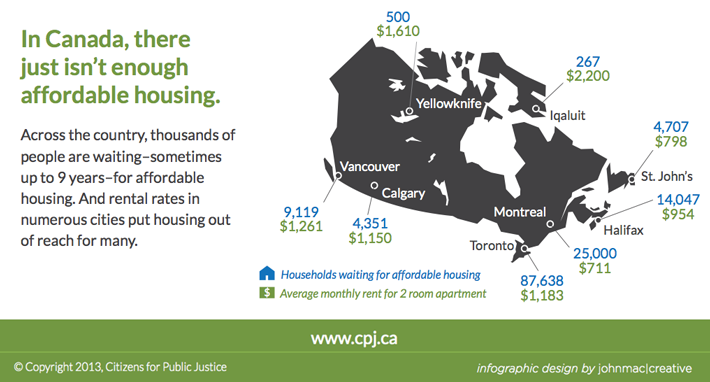

Citizens for Public Justice, put out a good infographic about the lack of affordable housing. It stated that, “Across all of Ontario, for example, there are 156,358 households waiting for affordable housing. While it varies by location and household type, the average wait time in Ontario is two to four years. Some groups (mostly seniors) are housed within a year, while others (mostly singles and childless couples under 65) wait up to 10 years. Similarly, in Vancouver, the average wait time is 16 months and in Halifax it is approximately three years.”

According to FCM’s Housing Crunch campaign, while 1/3 of Canadians are renters only 10% of new housing built in the past decade has been rental units. Combined with “high home prices and record levels of household debt” it’s no wonder that the Bank of Canada calls “the imbalance in the housing market the number one domestic risk facing the economy.”

But it’s not all bleak.

Wellesley Institute has an amazing e-map of local housing initiatives across the country broken down into several categories including: Policy and Information, Service Providers, Shelters, Networks and Resource Links. It shows the dedication and the multiplicity of programs and initiatives across the country.

In British Columbia, their housing strategy Housing Matters BC is touted as the "most progressive housing strategy in Canada. With a focus on those in greatest need, our government has invested more than $2.5 billion into housing programs since 2006 and transformed affordable housing in British Columbia. Since its release, the Province has doubled the number of shelter spaces, added thousands of affordable units for seniors and people with disabilities and seen a significant reduction in the number of unsheltered homeless. Today, more than 98,000 households benefit from provincial affordable housing programs — a 20 per cent increase since 2006."

There are new housing projects being developed and funded under the Homelessness Partnering Strategy (HPS). HPS itself was renewed for several years with a focus on Housing First. We know from research that Housing First is a successful model for housing people experiencing homelessness. The use of rent supplements, in the absence of new affordable housing units, will be key for its successful implementation across the country. Tools such as the Housing First in Canada: Supporting Communities to End Homelessness e-book and the web-based Housing First tool-kit will be useful for communities.

It’s just not enough!

[1] Calculation $11.00/hr minimum wage x 40 hours = $440/week x 4.33 weeks =$1905.20/month (gross) x 12 months = $22,862.40/annually.

This post is part of our Friday "Ask the Hub" blog series. Have a homeless-related question you want answered? E-mail us at thehub@edu.yorku.ca and we will provide a research-based answer.