Take a moment to imagine yourself strolling along a quiet, suburban street. Now picture a busy, downtown street. The experience and sights are obviously quite different.

One of the most obvious, and certainly visible, differences is the physical contrast between the two settings. When we think of the suburbs our imagination pictures a place filled with large single detached homes, expansive green lawns and meandering residential streets. The city, on the other hand, brings up images of a place dominated by tall buildings, crowded sidewalks and a checkerboard-style street layout. While these differences are easily understood by anyone who has experienced both places are the physical differences the only elements that separate the suburbs from the city?

The answer is a definite “No!”

Social scientists often point out that the spaces where we live influence our lives and behaviour.

Many of us will be well acquainted with the suburbs depicted in early sitcom shows such as ‘Leave it to Beaver’, or more recent examples such as ‘Modern Family’. Most of us might also be familiar with the unique urban communities found in many cities such as ‘Chinatown’ or ‘Little Italy’. These examples provide us with an illustration of the diversity found in cities and give us an idea of how suburban and urban areas vary from one another.

One specific difference is the concentration of the homeless population within cities. In the last half of the 20th century in American cities there tended to be a concentration of people (including those with addictions, the elderly, criminally involved, the poor, the disabled and the homeless) in areas known as 'skid rows'. This was less prevalent in Canada and while there were areas of concentration, with the exception of the Downtown Eastside in Vancouver there was rarely a 'skid row' in Canadian cities.

While there is little doubt that homeless people could be found in all communities we should consider the following question: Where would you expect to see a homeless person: on a downtown street corner at a busy intersection or on a cul-de-sac in a suburban neighbourhood?

Most people would probably agree that the street corner scenario is a more likely setting to see a homeless person. This observation has been supported by a great deal of research over the years.

For example, in 1990 the U.S. Census Bureau did their first complete, national count of the homeless population. They not only attempted to count the total population, but they also mapped the locations and concentration of homelessness.

A few important facts about homelessness back then emerged. Despite ongoing economic and political forces, a pattern of concentration was still present in the U.S. Also, the majority of the homeless population was concentrated in the most heavily urbanized areas.. For example, some of the largest cities (i.e. Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York) had areas where homeless people made up the majority of a neighbourhood’s population!

Another study, nearly two decades later, investigated how the total homeless population in the U.S. is spread across the country. It revealed that ‘completely’ urban areas housed approximately 77% of the total U.S. homeless population compared to 4% in completely rural areas. It also found that ‘major cities’ (population larger than 500,000) account for 51% of the homeless population in metropolitan areas despite only accounting for 34% of the total population in those same areas.

In The Geography of Homelessness, Richard Florida and Charlotta Mellander tried to figure out which characteristics of an area are related to higher rates of homelessness. Looking at various cities across the U.S. they found that higher housing costs and higher population density are connected to larger concentrations of homeless people. And, as one might guess, these characteristics are typical of urban centres in most North American cities.

None of these studies really give us the full picture however. While figuring out where homeless people concentrate is important, determining why this pattern exists is an even more crucial question. Unfortunately, Florida and Mellander do not adequately address this question. For example, one finding in their report demonstrates that cities with warmer climates have higher rates of homelessness but we can’t just assume that means that warmer climates cause homelessness.

Dear and Wolch, in their book Landscapes of Despair, provide a clue as to why homelessness might be concentrated in cities rather than its suburbs. They started by looking at the location of public institutions such as homeless shelters, food banks and other organizations that support and provide relief for low-income and homeless people. What they found was that there was a noticeable trend. This pattern showed that these public institutions are concentrated in relatively small, urbanized areas of cities. These ‘zones of dependence’, are created because in the pursuit of accessing often-limited social services provided by a city, homeless people naturally are attracted to the few areas that offer such resources. In return, new services then locate themselves where their client base is.

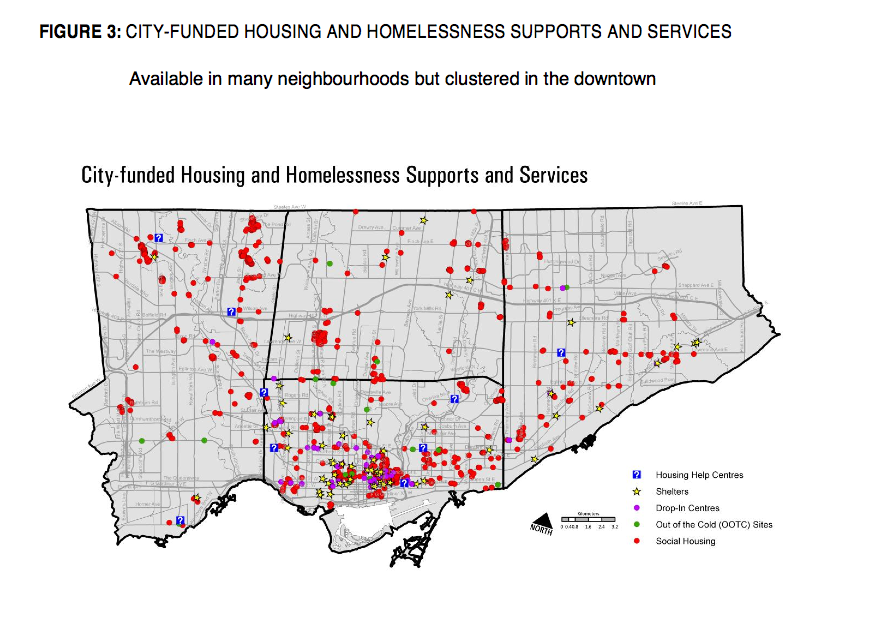

Toronto’s 2014-2019 Housing Stability Service Planning Framework published by the Shelter, Support & Housing Administration department, provides some strong evidence that this concept might also be applicable to Canadian cities as well (see their Figure 3).

Looking at the central area of Toronto and comparing it to the inner suburbs, we can see that there is a definite concentration of social services. If one focuses on those services that almost exclusively cater to the homeless—shelters and drop-in centres—the concentration becomes even more apparent.

Kingston’s 10-Year Municipal Housing and Homeless Plan provides a similar map which highlights where homeless people can find resources such as shelter or drop-in centres. Looking at figure 2 on page 71 from the document, we can see that these resources have—much in the same fashion as Toronto—been concentrated in the more urbanized area of Kingston.

With some confidence then, we can say that Dear and Wolch’s ‘zone of dependence’ is probably the rule rather than the exception, regardless of the size of the city. This ‘concept is, of course, only one of many reasons why homeless people might concentrate in urban areas. However, this particular concept is still important because it represents a piece of the puzzle, which allows us to understand why this pattern exists.

If we reflect on the walk we took at the beginning of the blog, it should now be easier to understand why we are more likely to spot someone who is homeless during our walk along an urban city street than along a winding road in the suburbs.

We'll be chatting more about this topic today at 1PM - 2PM (ET) in our monthly tweet chat. Follow #HHChat and join our conversation.