A common misconception that pervades discourse about causes of homelessness and poor households is the belief that individuals live in poverty because they choose to be unemployed. Time and time again, research has shown that this is simply not the case. Perhaps a more important question to ask is: does poverty persist in households where individuals are employed?

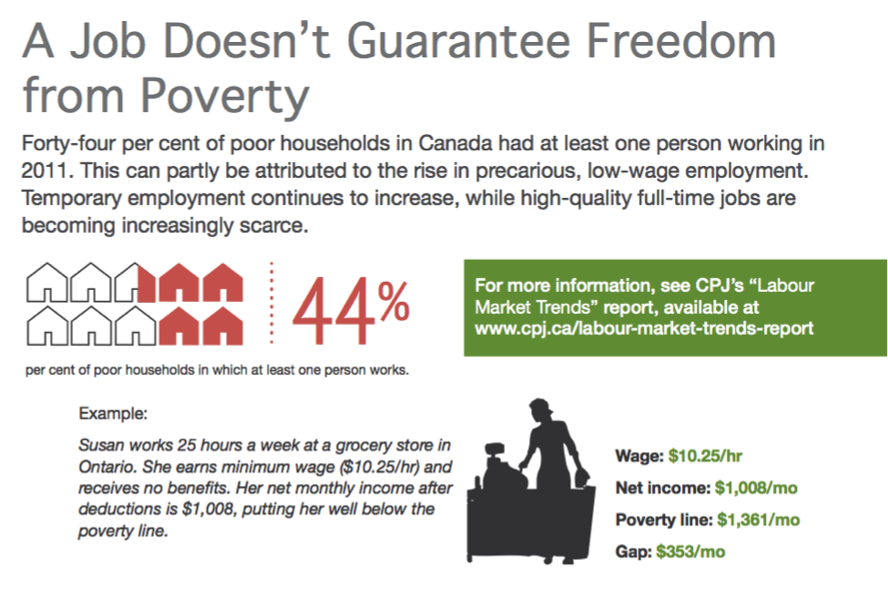

The infographic above, published by the Citizens for Public Justice, answers this question. A job alone does not guarantee freedom from poverty. In fact, in 2012, at least one member of the household was employed in a staggering 44% of all poor households. Even in situations where an individual is employed, there may still be the need for income supplements, as well as educational and employment supports.

This is partially because of the monumental changes that have occurred in the Canadian marketplace. The growing trend that continues to emerge is precarious employment: a decline in the number of well-paid jobs, and an increase in both lower-paying jobs and temporary employment. The infographic provides an example of how an individual working part-time, at minimum wage, falls below the poverty line. Temporary employment, by its very nature, often results in incomes that are unpredictable, making households more prone to suffering from fluctuations in income. In households where families and individuals are living paycheque to paycheque, these trends are direct contributors to family poverty.

Income supplements are essential to lifting families above the poverty line. While the idea of implementing guaranteed annual incomes (GAIs) has been around for decades, it has recently resurged as a result of the rising costs associated with dealing with the symptoms of poverty rather than its causes. GAI refers to various proposals that look to implement a guaranteed minimum income for Canadians, related to the concept of a negative income tax. GAIs will provide struggling Canadians with some security from income shock. The most common criticism associated with GAIs is that such models would act as a disincentive to work. Emery, Fleisch and McIntyre argue that this doesn’t mean a GAI scheme for Canada should be rejected, instead this only means that the uncertainty over GAIs should be “used to guide a phased-in introduction of a GAI with the intent of determining the extent of the ultimate coverage of the scheme."

Educational and employment supports work hand in hand to support communities across Canada. Educational supports can help provide individuals with specialized skills that are easier to market. Employment supports, in turn, can help these same individuals improve their chances of finding a well-paid stable job.

It's important to keep in mind that employment percentages on their own are unlikely to be a clear indicator of what causes homelessness. Details about the nature of employment, and the income generated from employment are far more useful metrics. A recent paper, published by the University of Calgary's School of Public Policy, posits household food insecurity as a useful consumption-based indicator of both poverty and lack of insurance against income shocks. Just as the causes for poverty in Canada are multidimensional, solutions in turn have to be multidimensional and have to account for more than just one metric.